In order to define the “female gaze” in art, one must first understand the historical narrative established long before modern times. The measure for representing the female nude in the Western art canon was presented by the male artist specifically for the male viewer. Laura Mulvey theorized this viewpoint in cinema and her idea was adapted by John Berger in art history. Due to limited support and opportunity for females as artists, the active role in representing (as opposed to being represented) was almost non-existent for women. There was a male monopoly representing the nude female form. This “male gaze” tended to showcase women as passive, sexual objects illustrated for one’s viewing pleasure. Berger explains, “It is worth noticing that in other non-European traditions … nakedness is never supine in this way. And if, in these traditions, the theme of a work is sexual attraction, it is likely to show active sexual love as between two people, the women as active as the man…” (53). In Europe, only in the late 1800s were women allowed to draw from live models in the Royal Academies. Prior to this the only known representations of female nudes were created by men exhibiting the male gaze.

Femme representation by femmes is a modern concept. Only with the push back from marginalized groups functioning in a white male dominated patriarchal society did we see the beginnings of change. With women given the room to inform themselves with artist training, they began to represent other women (and themselves) in ways that were more attune to female experience. Representations of femininity began to crop up whether highlighting motherhood, female kinship, or daily activities. These representations were not overly sexualized and the women were not passive objects to merely be looked at. In the early 1900s, women representing other women both clothed and nude was taken even further.

Paula Modersohn-Becker’s (1876 - 1907) is credited to be the first woman artist to paint a nude self-portrait.

Self-Portrait with Amber Necklace, 1906, is framed like a classic portrait from the waist up. The artist holds a flower in each hand, wears flowers in her hair, and is presented in a garden. She renders herself in a simplified manner with a flatness to the form. The figure does not look directly at the viewer but away in seeming contemplation. The viewer is privileged to see the woman in a private moment where she simply exists in nature. There is no sexual glance at the viewer or languid “take me” attitude projected outwardly as often seen in the male gaze. The subject just simply is. Another painting by the artist,

Mother and Child Lying Nude, 1907, presents the female nude in an intimate moment of motherhood. As the mother and child rest, there is a sensitivity projected to the viewer. Prior to representing an anonymous mother, the painter depicted herself pregnant and partially nude a year earlier. Modersohn-Becker’s paintings provide a more holistic representation of women. The nude figures represented are honestly existing in their natural states without the concern of gratifying the viewer.

Paula Modersohn-Becker, Self-Portrait with Amber Necklace, 1906

While Modersohn-Becker is likely the first female to paint a nude self-portrait, the legacy of nude self-portraiture for womxn reverberates to today. The femme exploration of the nude self-portrait is not unique to painting. Laura Aguilar (1959 - 2018) was an American photographer. Her work mainly focuses on representing marginalized groups. As a full-bodied, queer, Latinx woman, the artist was no stranger to prejudice. Her

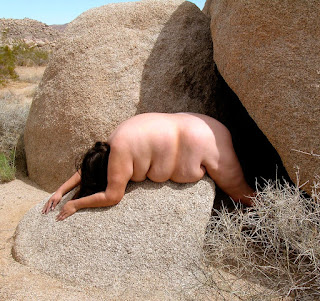

Grounded series is a wonderful collection of photographs of the artist nude within the desert landscape. The photographer chooses to continue the legacy of presenting women in conversation with nature. The positioning of her strong, full-figure amongst the rocky boulders is reminiscent of the Venus of Willendorf figurine. It brings sentiments of time when women were valued more equally for their function within nomadic tribes of the Paleolithic era. To learn more about Aguilar’s series, read

this short article.

Laura Aguilar, Grounded "Untitled", 2007/2016

Laura Aguilar, Grounded #111, 2006/2016

Laura Aguilar, Grounded #112, 2006/2016

Contemporary artist, Alonsa Guevara (b.1986), positions the nude form in context to nature as well. In her series,

Ceremonies, the artist paints the female nude in a bounty of fruits. The series began in 2015 with a triptych that included her sister, brother, and herself. Her brother is the only male represented in the three-year long series thus far. Guevara’s

After My Ceremony shows the artist lying nude on her side with eyes closed. The scene is peaceful as the subject rests in a natural splendor. In a Forbes interview, Guevara expresses, “I am trying to make work that makes the viewer feel that connection and that love for nature and their own spiritual beliefs. It doesn’t need to be a specific religion, but rather about the strength of existence. I’m trying to create kind of sacred objects and sacred moments” (Hervey). The artist does just that. The series includes women in different stages of womanhood including pregnant women and nursing mothers. The incredibly detailed and colorful works present nude women with the same respect and regard the artist portrayed in her original nude self-portrait. To see more of this fantastic series, check out the artist's

website.

Alonsa Guevara, Sibling's Ceremonies, 2015

Alonsa Guevara, After my Ceremony, 2015

Another artist whose nude self-portraits create a modern sense of spirituality is Sullivan Giles (b.1986). In her latest work,

Self Portrait at 32, the artists represents her tattooed-clad body staring at the viewer with hands delicate and open. The positioning reminds me of the ecclesiastical imagery normally used for the Virgin Mary. The figure is relaxed and welcoming against a printed background similar to wallpaper. An earlier version,

The Body as Home, represents the artist looking away from the viewer with hands touching her hair. The positioning of the figure in this painting is more reserved. The subject seems to be preoccupied with her thoughts where the second painting is confrontational. Comparing the two paintings, the subject seems more comfortable in her own skin in the second rendition. The subject shows the viewer a presence that is confident yet not boastful. It shows the artist existing as is, complete.

Sullivan Giles, The Body as Home, 2018

Sullivan Giles, Self-Portrait at 32, 2019

An early work by artist, Emma Hopkins, evokes a different feeling with her nude self-portrait.

My Shadow presents the female nude in a dark manner. There is a revealing of her shadow-self in the painting. The large beast-like figure formed by her shadow, creates a sense of angst and discomfort. In society womxn are projected as beautiful and graceful. Mainstream culture provides a harmful standard of perfection for femmes. The artist is embracing her imperfections or darkness by exposing this aspect of her being to the viewer. Again, this is a more holistic representation of the female experience. Womxn are incredible but not perfect. The artist shows the humanity in femininity with the work.

Emma Hopkins, My Shadow, 2016

The representation of womxn by womxn is far-reaching from the sexualized, objectified representation of womxn by men. While the male gaze still strongly exists in contemporary art today, there are more representations of a counter-narrative. Art continues to push ideas further to include more accurate depictions of femme experience. The integration of many examples of femininity by womxn themselves allows for a more comprehensive representation of womxn at large. The female gaze is a narrative that creates space for womxn of all kinds to exist in society. While a single woman may not identify with every representation out there, having many models of femininity allows for womxn to have agency in feeling comfortable in their own skin, feeling confident in their identity, and accepting all parts of their being--whether dark, sensual, sexual, maternal and spiritual alike. Representation of the female gaze is incredibly important and here to stay.

Works Cited

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. British Broadcasting Corporation, 2008.

Hervey, Jane Claire. "How Painter Alonsa Guevara Navigates Social Media, Taboos and Sustaining

Her Art."Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 9 July 2018,

www.forbes.com/sites/janeclairehervey/2018/07/08/how-painter-

alonsa-guevara-navigates-social-media-taboos-and-sustaining-

her-art/#14dc600743aa.

No comments:

Post a Comment