In the beginning of the semester, as curious students not knowing what to expect from the course, we were required to create a mini post about critical artist expression. More specifically, we were to find and research a female artist, who produces controversial mediums of work and addresses cultural, social, or political issues. I was unsure of who to talk about and focus a whole post about, until I did my research (of course, that’s apart of the assignment) and stumbled across a vast majority of incredible female artists, making it hard to just pick one, which sparked my interest through the entire course. It made me want to learn more. It’s so hard to pick just one because they’ve all made a tremendous impact in the art world, breaking ground so that women can have a fair shot in a world dominated mainly by men. I decided to focus more on African American female artist and how they reclaim the identity of Black women in their arts, despite issues of race, sex, and power being seen as a barrier.

Renee Cox

|

| Renee Cox, Chillin' with Liberty, 1998 |

Taking the assignment all the way back to January brings me to first person out of five other female artists I’d like to acknowledge, Renee Cox. Being a well-known African-American female artist, Renee Cox uses her talent to bring specific issues, that people turn a blind eye to, to the forefronts of our psyche, so that we can acknowledge them, learn more about it, and hopefully do something to remedy the problem. Much of her work addresses problems in regards to black women and their continuous run in with sexism and racism. To make a statement, Cox uses herself as the subject of her art work. Throughout the semester, we spoke heavily about the male gaze and the female gaze, as well as the clear distinctions between both the gazes. To recount, the male gaze oversexualizes women, objectifying them, looking at women and how they may be perceived. This then effects how women look and define themselves. The female gaze is the complete opposite because it allows women to take back their own sense of representation and even though the gaze still focuses on the female body and overall image, women are in complete control of what they want to be portrayed. Cox embodies the female gaze greatly, exceeding limits and taking her work to new heights, throwing away the idea of being conservative. Cox is always serving up “raunchy realness”, presenting social issues in a way that makes people uncomfortable, but still discussion worthy. With the tantalizing series of photos that Cox creates, she pushes the limits and uses her nude body to empower black women and normalize this idea of sexuality within black womanhood, a topic that’s also rarely discussed. In doing that, Cox also follows through the rest of her agenda, aiming to target the stereotypes that linger in the African American community, take them back , and switch up the meaning of all of them.

Mickalene Thomas

|

| Mickalene Thomas, Three Graces: Les Trois Femmes Noires, 2011 |

Mickalene Thomas, similar to Renee Cox, uses the concept of female gaze, using Black women as the nexus of her artwork. Mickalene Thomas views her subjects-- black women-- as a reflection of herself and many other women of color struggling with ideal standard of what’s beautiful and who/what is deserving enough of being titled beautiful. Thomas values the confidence and how they carry themselves as women. The subjects in Thomas art are staged in constructed environments decorated with vintage patterned fabrics, furniture and objects. Thomas’ skillful employment of patterns, bold colors and lush textures are used to emphasize and glorify her subjects. Most of the work produced by Thomas alludes other artist, for instance, “The Three Grace”created by Raphael. The title of this piece refers to the three fertility goddesses worshipped by the Greeks and Romans during that era. Raphael’s “The Three Graces” shows the three goddesses of Greek and Roman myth, Aglaea, Euphrosyne, and Thalia dancing together in a meadow. Raphael portrays his subjects in harmony with one another, as well as beauty and charm, but not many pick up on the fact that he is portraying a male gaze. Raphael is portraying women through how he believes or expects them to be, docile, pure, innocent creatures. Looking at Thomas’ "Three Graces: Les Trois Femmes Noires", it draws inspiration from Classical art, art created by the ancient Greeks and Romans.you can immediately see the influence of African American art history. The influence of 70’s black culture through the three grace’s appearance. Their hair, jewelry, and attire alludes back to how African Americans were portrayed in 70’s black action films and other types of media. The three graces depicted here explore African American notions of beauty, influenced by Harlem Renaissance artists. Thomas uses bright, vivid colors in the background of her mosaic just as many Harlem Renaissance painters did. By including these references to black art history in her "Three Graces", Thomas is trying to make some connection between black beauty and art history.

Betye Saar

|

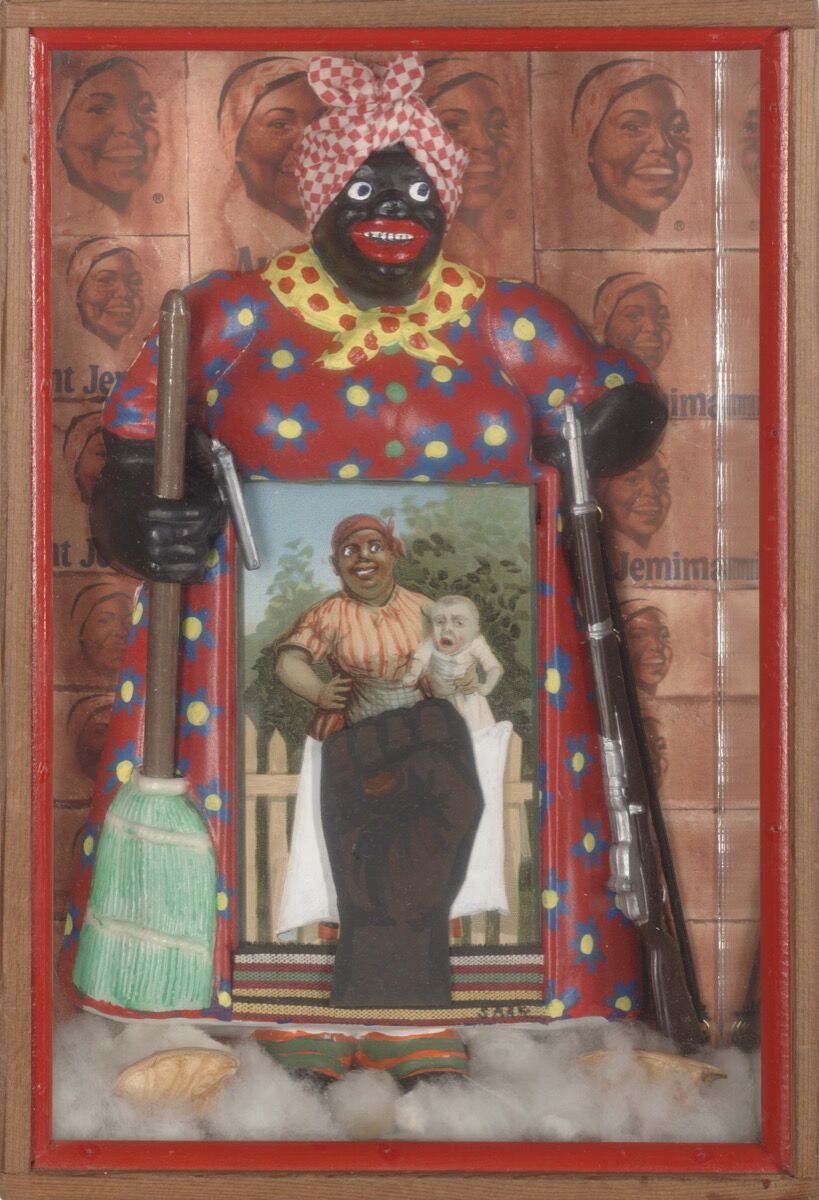

| Betye Saar, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, 1972 |

Betye Saar also tries to uplift Black women in her art pieces. Saar does so, by not only acknowledging the oppressive behavior or the results of it, but by also making an effort to remove the racially charged stereotypes that society often time associate with them and combat. Sars is also known to “[collect] derogatory images of African Americans… as a way of understanding how Whites have historically defined Blacks—as caricatures, as objects, and sometimes as less than human” ( RACE/ETHNICITY 3). For instance, in her most controversial piece entitled The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, she delves deep into the way Black women were portrayed during the 19th century, particularly through the mammy figure. The mammy figure was oftentimes seen as asexual, “portrayed an obese, coarse, maternal figure”. In regards to the family she was pictured serving, “[the mammy] had great love for her white "family," but often treated her own family with disdain” (Pilgrim 1). Saar uses these type of objects/image as the focus of her art work as a means to reclaim them from individuals who used it as a means of oppressing and belittling the African American community.

|

| Kara Walker, African/American, 1998 |

Kara Walker’s work is similar to Betye Saar, in which some of the work that she produces also centers itself in the 19th century, where she “uses black-paper silhouette cut-outs to construct imagery that mingles ‘the most deeply disturbed fantasies of Southern whites with the hitherto unimaginable visions of a contemporary young African-American woman’” (Cullum, 1995 as cited in Artspace Editorial, 2017). Walker uses the cut-out images to address issues that revolved around, not only gender, but also race, similar to the other artist discussed above. She brings the concept of gender and race to portray the relationship it has with power and the dynamics surrounded by it.

Howardena Pindell

|

| Howardena Pindell, Free, White, and 21, 1980 |

Works Cited

“Artwork Detail.” Artwork Detail | Kemper Art Museum, www.kemperartmuseum.wustl.edu/collection/explore/artwork/12845.

Artspace Editorial. “6 Black Radical Female Artists To Know Before You See ‘We Wanted A Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85.’” Artspace, 7 Apr. 2017, www.artspace.com/magazine/art_101/book_report/6-black-radical-female-artists-to-know-before-you-see-we-wanted-a-revolution-black-radical-women-54692.

BIOGRAPHY | renee-cox. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.reneecox.org/about#!

RACE/ETHNICITY, www.bluffton.edu/homepages/facstaff/sullivanm/race/race4.html.

“The Mammy Caricature.” The Mammy Caricature - Anti-Black Imagery - Jim Crow Museum - Ferris State University, www.ferris.edu/jimcrow/mammies/.

Web Gallery of Art, Searchable Fine Arts Image Database, www.wga.hu/frames-e.html?/html/r/raphael/2firenze/1/21graces.html.

No comments:

Post a Comment